We need to start with some data.

We will generate a list of data on the calculator using

GNRND4 with Key 1=131425002 and Key 2=1100026. That list

will be the same numbers that appear in the following table:

Thus, our problem will be to generate a frequency table for the data in the

list above.

Figure 1

| We begin by getting the data into the calculator.

We could do this by entering each of the 51 values into the calculator.

This, however, is prone to error.

A better way is to take the option of running the GNRND4 program.

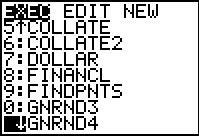

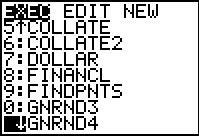

We need to start the GNRND4 program. To do this we open the Program Menu by pressing the

key. The resulting screen start the list of

programs that are on the calculator being used.

In this case, the calculator has quite a few programs, enough so that we cannot see the desired GNRND4.

Therefore, we use the key. The resulting screen start the list of

programs that are on the calculator being used.

In this case, the calculator has quite a few programs, enough so that we cannot see the desired GNRND4.

Therefore, we use the  key to move down the list. key to move down the list.

|

Figure 2

|

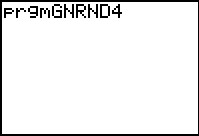

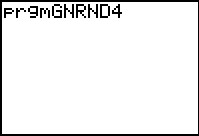

In Figure 2 we have found the GNRND4 program. It is beyond the numbered positions.

However, since it is the program selected by the cursor, we can

press the  key to cause the program

command to appear on the main screen, as shown in Figure 3. key to cause the program

command to appear on the main screen, as shown in Figure 3.

|

Figure 3

|

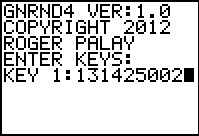

Notice that the calculator has automatically placed the characters "prgm"

before the name of the program we want to run. All that remains now is to

press the  key again to start the program. key again to start the program.

|

Figure 4

|

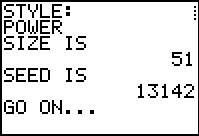

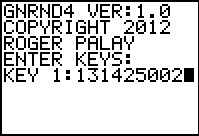

The program starts by displaying some vital information.

Then the program prompts for the Key 1 value.

In the example we are using we need to enter 131425002

in response to that prompt. Figure 4 shows the screen after we have

entered that value. Then we press the  to continue the program.

to continue the program.

|

Figure 5

|

Now GNRND4 is asking for the second key value: we respond with the value 1100026.

Then we press the  to continue the program.

to continue the program.

|

Figure 6

|

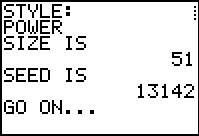

As shown in Figure 6, the GNRND4 program then displays some data

about the process it is running. The pargram then waits in a "pause" state,

for us to press the  key in order to continue. key in order to continue.

|

Figure 7

|

Continuing, the program displays more data, again waiting for us to

press the  to go forward. to go forward.

|

Figure 8

|

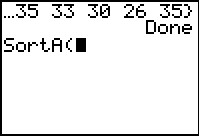

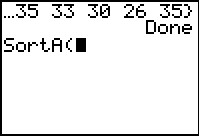

After Figure 7 and before Figure 8, the calculator displays a screen that slowly fills with dots. That screen, which I cannot capture

so that I can display it here, just lets you know that the calculator is continuing to work

on the task. Once the task is completed, the calculator erases the screen of dots and displays the

list of values that has been generated. Figure 8 shows this list. The calcualtor is in a "pause"

state (note the pattern of dots in the upper right corner of the screen).

This allows us to use the left and right cursor keys to move through the entire list.

|

Figure 9

|

To move from Figure 8 to Figure 9 we have used the  key

a number of times. Note that starting in Figure 8 and continuing in Figure 9, the numbers in our

list are identical to the numbers given in the table above. key

a number of times. Note that starting in Figure 8 and continuing in Figure 9, the numbers in our

list are identical to the numbers given in the table above.

|

Figure 10

|

For Figure 10 we have pressed the  key again and again to move to the very end of

the list. Here we can see that the end of the list corresponds to the end of the values in the table above.

Note that the program is still "running" although it continues to be in the "pause" state.

To finish the program we need only press the key again and again to move to the very end of

the list. Here we can see that the end of the list corresponds to the end of the values in the table above.

Note that the program is still "running" although it continues to be in the "pause" state.

To finish the program we need only press the  key. key.

|

Figure 11

|

Figure 11 shows that the program has completed. We can no longer scroll through the values in our

list.

However, the list that was generated in stored in the calculator in L1.

|

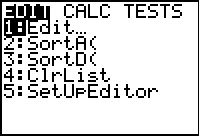

Figure 12

|

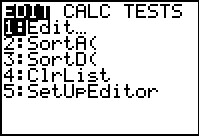

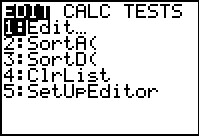

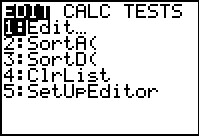

One way to examine the contents of L1 is to

use the STAT

editor. To get to this we press the  key to bring up

the display shown in Figure 12.

The option that we want to select

from this is the first one, Edit..., and its

number, 1 is already highlighted. Therefore, we can either

press the key to bring up

the display shown in Figure 12.

The option that we want to select

from this is the first one, Edit..., and its

number, 1 is already highlighted. Therefore, we can either

press the  key or the key or the

key to start that option. key to start that option.

|

Figure 13

|

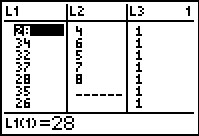

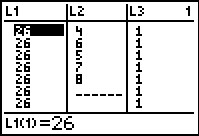

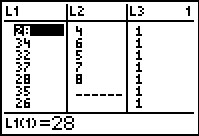

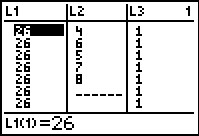

Figure 13 shows the Editor. We are interested in examining

L1. (The calculator used here had some previous use

for L2 and L3,

but we ae not concerned about those values.) Figure 13 shows the

first 7 items in L1, along with

not only highlighting the first item but also making a specific

reference to it at the bottom of the screen. We can use the

and and  keys

to move through the items in L1. keys

to move through the items in L1.

|

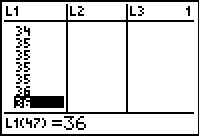

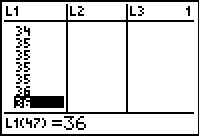

Figure 14

|

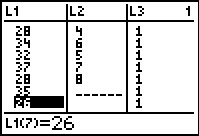

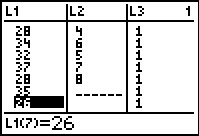

For Figure 14 we have moved the highlight to the seventh item in L1.

We can continue using the  key to display

more items in the list. In this case, we will use that key to move

all the way to the bottom of the list, shown in Figure 15. key to display

more items in the list. In this case, we will use that key to move

all the way to the bottom of the list, shown in Figure 15.

|

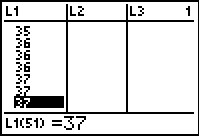

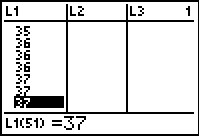

Figure 15

|

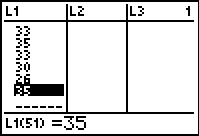

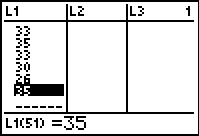

Here we are at the end of the list. Again we can compare the numbers in the list

to those in the original table of values given above to verify that we have exactly the same

values. To get out of the Editor we use the key sequence

.

This will return us to the screen shown in Figure 16. .

This will return us to the screen shown in Figure 16.

|

Figure 16

|

Having seen the list of values in L1,

we are ready to start working with that list in order to produce a frequency table.

The approach here will be to sort all of the values so that we can

merely move through the list, observing each different value

and counting the number of times each different value is in the list.

To sort the list into ascending order we need to get to the SortA( command. We will

find that command in the LIST menu, and we get to that

menu via the key sequence

. .

|

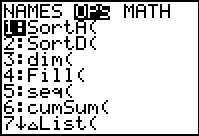

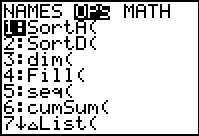

Figure 17

|

Figure 17 shows the LIST menu, or rather, the NAMES

sub-menu of the LIST menu. We could use this sub-menu to select a name of a list that

is defined on this calculator. The option that we want is in a different

sub-menu, in particular, it is in the OPS sub-menu. To get there we

use the  key. Moving us to Figure 18. key. Moving us to Figure 18.

|

Figure 18

|

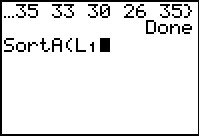

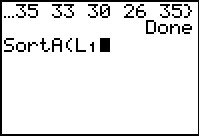

Figure 18 shows the OPS sub-menu. We have the desired SortA(

option here. Since that is the option that is

highlighted, we select that option by pressing the

key. key.

|

Figure 19

|

Having selected the option, the command SortA( has been pasted onto our screen.

We need to give the calculator the name of the list to sort into ascending order.

We can specify the L1 list by using the

key sequence   . .

|

Figure 20

|

Now the command is almost complete. We can press the  key to add the closing right parenthesis, shown in Figure 21.

key to add the closing right parenthesis, shown in Figure 21.

|

Figure 21

|

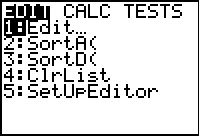

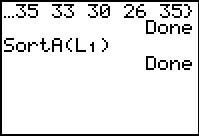

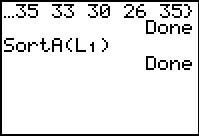

Having completed the command, we press the  to

perform the cammand. The calculator does the work and signals that it has

completed the work by displaying Done.

We want to return to examine the resulting sorted list.

To do that we return to the STAT menu

by pressing the to

perform the cammand. The calculator does the work and signals that it has

completed the work by displaying Done.

We want to return to examine the resulting sorted list.

To do that we return to the STAT menu

by pressing the  key. key.

|

Figure 22

|

To start the Editor we press the  key. key.

|

Figure 23

|

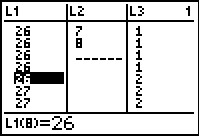

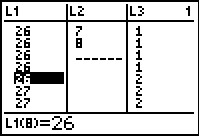

We can see here that the values in

L1 have been sorted.

In fact, we can see that the lowest value is 26. Now

we want to know how many 26's are in the list.

We use the  key to move down the

list, looking for the next different value. key to move down the

list, looking for the next different value.

|

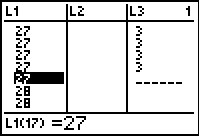

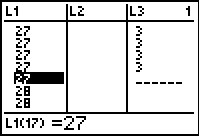

Figure 24

|

Figure 24 shows that we have found a new value, namely, 27

at position 9. Therefore, we know that we have 8 26's.

We could start our Frequency table with this information:

|

Figure 25

|

We left Figure 24 knowing that the next value is 27.

We move further down the list to see what follows 27.

In Figure 25 we see that the last 27

is in postion 17. Thus, we have 9 such values.

We can modify our table to be:

| Value | Frequency |

| 26 | 8 |

| 27 | 9 |

| 28 | |

|

Figure 26

|

Moving further down the table we see that we have 6 28's and

2 29. Thus we update the table to

| Value | Frequency |

| 26 | 8 |

| 27 | 9 |

| 28 | 6 |

| 29 | 2 |

| 30 | |

|

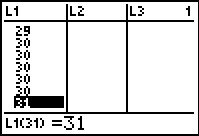

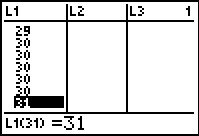

Figure 27

|

There are 5 30's.

|

Figure 28

|

There are 2 31's and 1 32.

|

Figure 29

|

There are 5 33's. Our table has grown to

| Value | Frequency |

| 26 | 8 |

| 27 | 9 |

| 28 | 6 |

| 29 | 2 |

| 30 | 5 |

| 31 | 2 |

| 32 | 1 |

| 33 | 5 |

| 34 | |

|

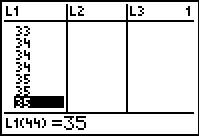

Figure 30

|

There are 3 34's.

|

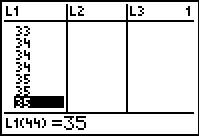

Figure 31

|

There are 4 35's.

|

Figure 32

|

There are 3 36's.

|

Figure 33

|

And there are 3 37's. (We recall that there are 51 items in the list. We saw this in

Figure 6 and in Figure 15. We could move down one more to verify that we are at

the end of the list if we wanted to do that.) Our final table becomes

| Value | Frequency |

| 26 | 8 |

| 27 | 9 |

| 28 | 6 |

| 29 | 2 |

| 30 | 5 |

| 31 | 2 |

| 32 | 1 |

| 33 | 5 |

| 34 | 3 |

| 35 | 4 |

| 36 | 3 |

| 37 | 3 |

|

Figure 34

|

We created the data in Figures 1 through 16.

We used a brute srength and awkwardness approach to

process the data in Figures 17 through 33.

The next section of this page gives an alternative approach to

that analysis of the data. We will run the COLLATE2 program

to mimic and add to the work we have done above.

First we open the program menu via the

key. We see that the program we want

is in position 6 of this listing. We can select that option

by pressing the "6" on the keypad. However,

we happen to know that the COLLATE2 program requires that the TOSTR2

program be on the calculator. (COLLATE2 calls TOSTR2 as a subroutine.)

In order to verify that the TOSTR2 program is loaded we use

the key. We see that the program we want

is in position 6 of this listing. We can select that option

by pressing the "6" on the keypad. However,

we happen to know that the COLLATE2 program requires that the TOSTR2

program be on the calculator. (COLLATE2 calls TOSTR2 as a subroutine.)

In order to verify that the TOSTR2 program is loaded we use

the  to scroll down the list of programs. to scroll down the list of programs.

|

Figure 35

|

Figure 35 shows that the TOSTR2 program is in fact present.

Even though the COLLATE2 program is not on the screen at the moment

we know that on this calculator the COLLATE2 program is currently

in position 6 in the list of programs. Therefore,

on this calculator, at this time,

we can select that 6thoption

by pressing the  key now.

key now.

|

Figure 36

|

The result of that action is to paste the command prgmCOLLATE2

on the screen, as is shown in Figure 36.

|

Figure 37

|

We press  to start the program.

The program clears the screen and prompts us for the name of the

list holding the values.

[Please note that Figure 37 shows the output from

Version 2 of the COLLATE2 program.) to start the program.

The program clears the screen and prompts us for the name of the

list holding the values.

[Please note that Figure 37 shows the output from

Version 2 of the COLLATE2 program.)

|

Figure 38

|

The list of values that we want to use is in

L1. We enter that name via the

key sequence   .

This enters the name at the end of the prompt, as is shown in Figue 38.

From there we press .

This enters the name at the end of the prompt, as is shown in Figue 38.

From there we press  to have the

calculator continue with the program. to have the

calculator continue with the program.

|

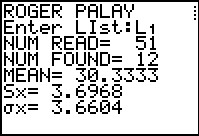

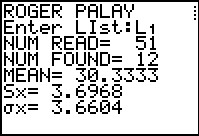

Figure 39

|

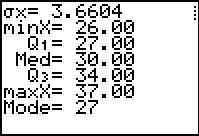

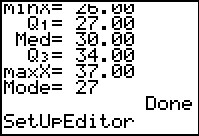

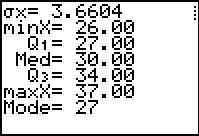

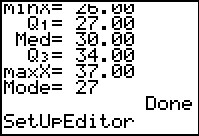

Figure 39 shows some of the output for the program. Note that it gives the

number of items in the list, and the number of different items in the list,

as well as some additional data. The program goes into a pause state at this point,

waiting for us to press  to continue. to continue.

|

Figure 40

|

Figure 40 gives the rest of the output from the program. This has two

pieces of information that are helpful to our current task,

namely, the low value (in this case 26)

and the high value (in this case 37). Again, noting the dots in the upper right corner, the program is in a paused state.

We can complete the program by using the  key. key.

|

Figure 41

|

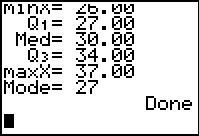

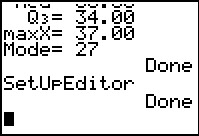

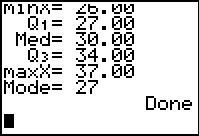

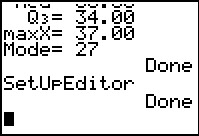

The program has finished its work and it displays the Done

in Figure 41.

Now, besides producing the output shown in Figures 39 and 40,

COLLATE2 also creates some new lists and the program changes the STAT Editor

to display these new lists.

|

Figure 42

|

To get to the STAT Editor we open the STAT menu via the

key.

Then we press the key.

Then we press the  key to start the editor. key to start the editor.

|

Figure 43

|

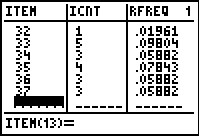

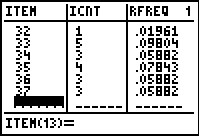

Comparing Figure 43 with Figure 23, we see that there are different lists being shown.

These new lists we created by the COLLATE2 program and they were put into the

STAT Editor by that same program.

ITEM, the first list, gives the different values that were in the original data list.

In effect, ITEM holds the first column of our frequency table, the column

giving the values found. Compare the conents of ITEM with the first

column of the frequency table shown above with Figure 33.

ICNT, meaning Item Count, holds the number of times each different ITEM

value was found. This is the "frequency" column of our frequency table. Aga9n, compare

the values under ICNT tot he values in the table to the right of Figure 33.

COLLATE2 has done our work for us.

We do recognize that we will need to use the  key to move down the editor to see the other values for our table. This

is shown in Figure 44.

key to move down the editor to see the other values for our table. This

is shown in Figure 44.

|

Figure 44

|

Here we see the remaining values and frequencies that we need to use.

To exit this screen we use the   key sequence. That will return us to the main screen.

key sequence. That will return us to the main screen. One additional activity for us will

be to return the Stat Editor to its default display. To do this we

press the  key to open the STAT menu, shown in Figure 45. key to open the STAT menu, shown in Figure 45.

|

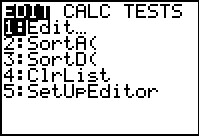

Figure 45

|

Here we see the STAT menu, and we have moved the highlight down to the

SetUpEditor option. We press the  to paste

tht option back onto the main screen. to paste

tht option back onto the main screen.

|

Figure 46

|

having pasted the command here, we press  to perform the command.

This command, without any additional lists being noted, will restor the

default setting for the Editor.

to perform the command.

This command, without any additional lists being noted, will restor the

default setting for the Editor.

|

Figure 47

|

The calculator has let us know that the command has been performed.

We can verify this by first returning to the STAT menu via the

key. key.

|

Figure 48

|

Then, prssing the  key will open the Editor, as shown

in Figure 49. key will open the Editor, as shown

in Figure 49.

|

Figure 49

|

We can see that the Editor has been returned to displaying the built-in Lists.

We can exit this via the   key sequence.

key sequence.

|

Figure 50

|

The following Figures demonstrate using the calculator with some degree of finess

to achieve the same results that we found first by brute strength and awkwardness, and tehn via the COLLATE2 program.

In particular, we will use the built-in feature of the calculator that

produces histograms of data, and we will force that display to give us the

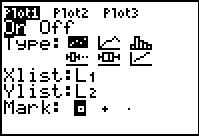

frequency of our values. We start by moving to the STAT PLOT

menu via the key sequence

|

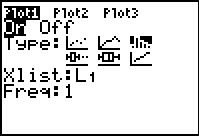

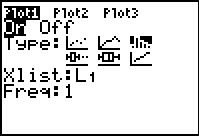

Figure 51

|

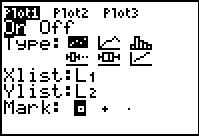

The particular calculator used here already had Plot1 turned on. We want

Plot1 turned on, but we also want to change a different setting for Plot1.

In order to make changes to the Plot1 values we press the

key. key.

|

Figure 52

|

In Figure 52 we see the options for Plot1. In particular, the plot is "On",

the type is set to a "scatter plot", and that scatter plot

will be of x-values stored in L1

and corresponding y-values stored in L2, with

the points of the plot marked by small squares. [Had Plot1 been turned "Off" we could

have turned it "On" by highlighting the "On" and pressing the

key. Since Plot1 is already "On" we will leave it alone.]

We want to change Plot1 to be a "histogram", the third Type in the first row

of Type options. Using the cursor keys we will move the highlight to that option. key. Since Plot1 is already "On" we will leave it alone.]

We want to change Plot1 to be a "histogram", the third Type in the first row

of Type options. Using the cursor keys we will move the highlight to that option.

|

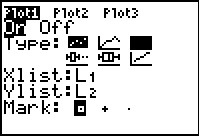

Figure 53

|

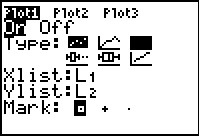

In Figure 53 we have moved the highlight to the

desired option. In this case we have captured the screen image as the blinking cursor was in

its all-black mode. To change the selection to this option

we press the  key. key.

|

Figure 54

|

Figure 54 shows that we have indeed changed the Type option. Note that this also changed the

rest of the screen so that the histogram will now be based on

the data in L1 and our grouping for the

height of each bar in the histogram will be 1.

We have set up Plot1 the way we want it. We can jump to the ZOOM

menu by pressing the  key. key.

|

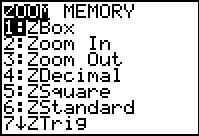

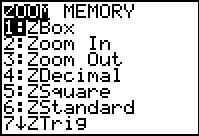

Figure 55

|

We have jumped to the ZZOOM menu because we want to use the ZoomStat

option. We want to use this option because it will set the WINDOW

values according to the data that is in our list. However, as you can see, ZoomStat

is not displayed on this screen. Instead we will need to use the

cursor keys to move down the menu to find

ZoomStat.

|

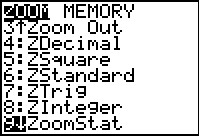

Figure 56

|

Here we have found ZoomStat in the menu and we have

left it highlighted. Thus, to perform the option we need only

press the  key. key.

|

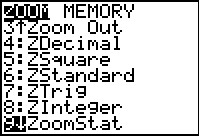

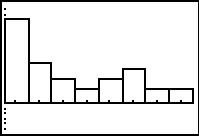

Figure 57

|

The result is the accurate histogram shown in Figure 57. This is a correct histogram but it is not the one we want.

We notice that it has 8 classes and we want 12. The problem is that the ZoomStat

option forced the calculator to make some choices on the width of the classes as well as on the

lower and upper limits on those classes. We want to revise that choice.

To do this we press the  key to open the WINDOW

menu. key to open the WINDOW

menu.

|

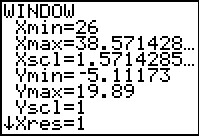

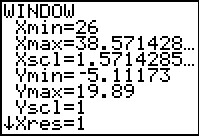

Figure 58

|

Figure 58 shows the WINDOW

values established by the data we have and the default

attempts of the calculator brought into play by the ZoomStat option.

We want to revise these settings so that each class will hold one and only one

of our 12 different values. Our changes are shown in Figure 59.

|

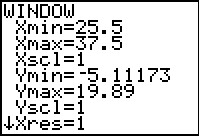

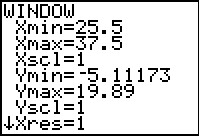

Figure 59

|

Now we have classes that are 1 unit wide, with the first class starting

at 25.5 and therefore ending just before 26.5. That class will hold any

of our values that fall in that range, which means that all of the 26's

will fall in this class, and none of our other values will be in this class.

We return to see a new historgram

by pressing the  key. key.

|

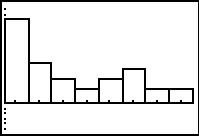

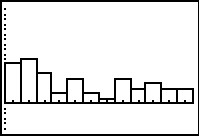

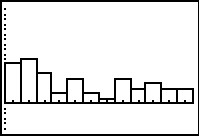

Figure 60

|

Figure 60 holds our revised histogram and it does have the 12 classes that we desired.

We would like to know the height of each of the rectangles because that height will be the frequency

of the value that the particular rectangle represents.

To see the height of each rectangle we will move into TRACE mode

by pressing the  key, after which we

see the information shown in Figure 61. key, after which we

see the information shown in Figure 61.

|

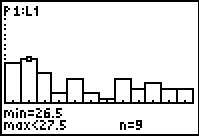

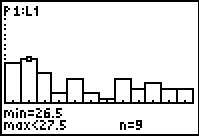

Figure 61

|

Now that we are in TRACE mode, the display in Figure 61 shows that for the first

rectangle on the graph, the rectangle represents values from 25.5 to 26.5, and that there were

8 values in our original data that fell into that range. Since the only value

in our original data that falls into this range is 26, we now know that the frequency of the B26's is 8.

|

Figure 62

|

In Figure 62 we have used the  key to move opur trace to the

next rectangle. The range for this rectangle is values from

26.5 to 27.5, and there were 9 such values.

Thus, the frequency of the 27's is 9. key to move opur trace to the

next rectangle. The range for this rectangle is values from

26.5 to 27.5, and there were 9 such values.

Thus, the frequency of the 27's is 9.

We can keep moving across the various rectangles to get

a frequency for each of the values in

our original table, and from this we could generate the same frequency table

that we constructed back in Figure 29.

|

Figure 63

|

Just to wrap up the display, Figure 63 shows the range and the count (frequency) for the final, rightmost,

rectangle on the histogram.

|

key. The resulting screen start the list of

programs that are on the calculator being used.

In this case, the calculator has quite a few programs, enough so that we cannot see the desired GNRND4.

Therefore, we use the

key. The resulting screen start the list of

programs that are on the calculator being used.

In this case, the calculator has quite a few programs, enough so that we cannot see the desired GNRND4.

Therefore, we use the  key to move down the list.

key to move down the list.

key to cause the program

command to appear on the main screen, as shown in Figure 3.

key to cause the program

command to appear on the main screen, as shown in Figure 3.

key again to start the program.

key again to start the program.

to continue the program.

to continue the program.

to continue the program.

to continue the program.

key in order to continue.

key in order to continue.

to go forward.

to go forward.

key

a number of times. Note that starting in Figure 8 and continuing in Figure 9, the numbers in our

list are identical to the numbers given in the table above.

key

a number of times. Note that starting in Figure 8 and continuing in Figure 9, the numbers in our

list are identical to the numbers given in the table above.

key again and again to move to the very end of

the list. Here we can see that the end of the list corresponds to the end of the values in the table above.

Note that the program is still "running" although it continues to be in the "pause" state.

To finish the program we need only press the

key again and again to move to the very end of

the list. Here we can see that the end of the list corresponds to the end of the values in the table above.

Note that the program is still "running" although it continues to be in the "pause" state.

To finish the program we need only press the  key.

key.

key to bring up

the display shown in Figure 12.

The option that we want to select

from this is the first one, Edit..., and its

number, 1 is already highlighted. Therefore, we can either

press the

key to bring up

the display shown in Figure 12.

The option that we want to select

from this is the first one, Edit..., and its

number, 1 is already highlighted. Therefore, we can either

press the  key or the

key or the

key to start that option.

key to start that option.

and

and  keys

to move through the items in L1.

keys

to move through the items in L1.

key to display

more items in the list. In this case, we will use that key to move

all the way to the bottom of the list, shown in Figure 15.

key to display

more items in the list. In this case, we will use that key to move

all the way to the bottom of the list, shown in Figure 15.

.

This will return us to the screen shown in Figure 16.

.

This will return us to the screen shown in Figure 16.

.

.

key. Moving us to Figure 18.

key. Moving us to Figure 18.

key.

key.

.

.

key to add the closing right parenthesis, shown in Figure 21.

key to add the closing right parenthesis, shown in Figure 21.

to

perform the cammand. The calculator does the work and signals that it has

completed the work by displaying Done.

We want to return to examine the resulting sorted list.

To do that we return to the STAT menu

by pressing the

to

perform the cammand. The calculator does the work and signals that it has

completed the work by displaying Done.

We want to return to examine the resulting sorted list.

To do that we return to the STAT menu

by pressing the  key.

key.

key.

key.

key to move down the

list, looking for the next different value.

key to move down the

list, looking for the next different value.

key. We see that the program we want

is in position 6 of this listing. We can select that option

by pressing the "6" on the keypad. However,

we happen to know that the COLLATE2 program requires that the TOSTR2

program be on the calculator. (COLLATE2 calls TOSTR2 as a subroutine.)

In order to verify that the TOSTR2 program is loaded we use

the

key. We see that the program we want

is in position 6 of this listing. We can select that option

by pressing the "6" on the keypad. However,

we happen to know that the COLLATE2 program requires that the TOSTR2

program be on the calculator. (COLLATE2 calls TOSTR2 as a subroutine.)

In order to verify that the TOSTR2 program is loaded we use

the  to scroll down the list of programs.

to scroll down the list of programs.

key now.

key now.

to start the program.

The program clears the screen and prompts us for the name of the

list holding the values.

[Please note that Figure 37 shows the output from

Version 2 of the COLLATE2 program.)

to start the program.

The program clears the screen and prompts us for the name of the

list holding the values.

[Please note that Figure 37 shows the output from

Version 2 of the COLLATE2 program.)

.

This enters the name at the end of the prompt, as is shown in Figue 38.

From there we press

.

This enters the name at the end of the prompt, as is shown in Figue 38.

From there we press  to have the

calculator continue with the program.

to have the

calculator continue with the program.

to continue.

to continue.

key.

key.

key.

Then we press the

key.

Then we press the  key to start the editor.

key to start the editor.

key to move down the editor to see the other values for our table. This

is shown in Figure 44.

key to move down the editor to see the other values for our table. This

is shown in Figure 44.

key sequence. That will return us to the main screen.

key sequence. That will return us to the main screen.  key to open the STAT menu, shown in Figure 45.

key to open the STAT menu, shown in Figure 45.

to paste

tht option back onto the main screen.

to paste

tht option back onto the main screen.

to perform the command.

This command, without any additional lists being noted, will restor the

default setting for the Editor.

to perform the command.

This command, without any additional lists being noted, will restor the

default setting for the Editor.

key.

key.

key will open the Editor, as shown

in Figure 49.

key will open the Editor, as shown

in Figure 49.

key sequence.

key sequence.

key.

key.

key. Since Plot1 is already "On" we will leave it alone.]

We want to change Plot1 to be a "histogram", the third Type in the first row

of Type options. Using the cursor keys we will move the highlight to that option.

key. Since Plot1 is already "On" we will leave it alone.]

We want to change Plot1 to be a "histogram", the third Type in the first row

of Type options. Using the cursor keys we will move the highlight to that option.

key.

key.

key.

key.

key.

key.

key to open the WINDOW

menu.

key to open the WINDOW

menu.

key.

key.

key, after which we

see the information shown in Figure 61.

key, after which we

see the information shown in Figure 61.

key to move opur trace to the

next rectangle. The range for this rectangle is values from

26.5 to 27.5, and there were 9 such values.

Thus, the frequency of the 27's is 9.

key to move opur trace to the

next rectangle. The range for this rectangle is values from

26.5 to 27.5, and there were 9 such values.

Thus, the frequency of the 27's is 9.